Gwendolyn Brooks in Our Neighborhood

Friday, July 24, 2020

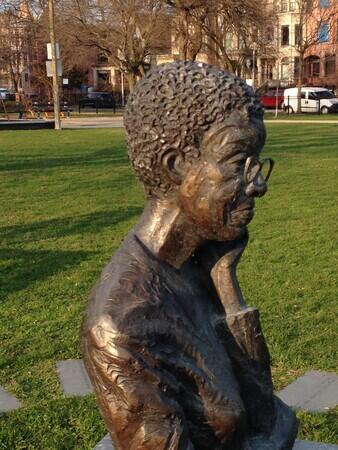

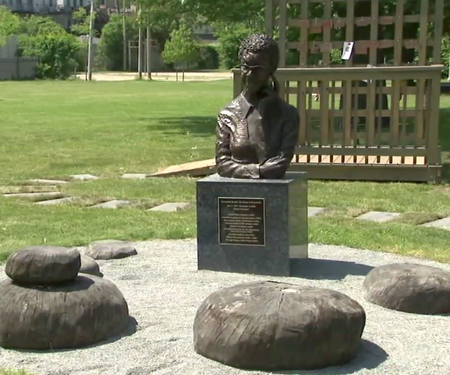

Gwendolyn Brooks, statue by Margot McMahon, 2018. Photos Rachel Cohen.

I originally wrote this entry on May 6, 2020, and have reposted it in conjunction with a new piece up at Literary Hub that continues the walking around this sculpture that goes on being so important to me. That piece is at:

Jane Austen, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Walking on the South Side

May 6, 2020

In our neighborhood, at 46th and Greenwood, is Gwendolyn Brooks Park. And in Gwendolyn Brooks Park there is a statue of the poet, which is believed to be only the second statue of an African-American woman in Chicago.

The sculptor is Margot McMahon, an artist who specializes in public projects and in sculptures of people who play what get called ordinary roles in the making of city life. The sculpture was McMahon’s idea, as part of the centennial celebration for Gwendolyn Brooks, and she approached Nora Brooks Blakely, daughter of the poet, who suggested that the park named for Brooks would be the right place, and then the two worked together to develop the sculpture and its installation. It was unveiled on June 6, 2018, the poet's birthday.

The statue of Gwendolyn Brooks shows the poet’s head, face, and glasses, and the upper part of her torso, arms and hands.

Installation photo from Margot McMahon's website, photographer uncredited.

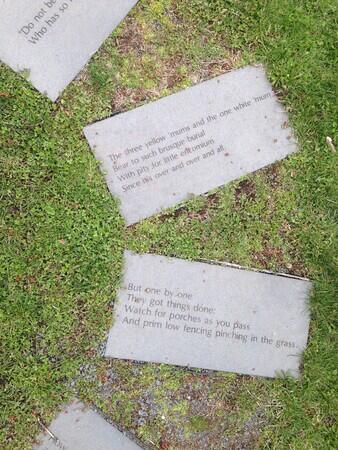

Behind is a wooden structure that is like the poet’s porch. Porch and figure are joined by a winding set of stepping stones that have inscribed on them quotations from Annie Allen, Brooks’s book of 1949 about the coming of age of Annie Allen, a book which won the Pulitzer Prize. Annie Allen is a very difficult modernist text that I have been learning to read for a few years now, and do not feel confident that I am yet really reading.

I am learning about this sculpture, as I am learning about the poetry, by visiting it many days in these months. It is of great value to me to have a thoughtful sculpture growing from a writer’s life that I can go and look at, and be in the space of.

*

Yesterday I wrote about Brook’s book of poems for and about children Bronzeville Boys and Girls with art by Faith Ringgold. It is interesting that in all Brooks’s work, as in Faith Ringgold’s, there is the sense of the presence and importance of children. Yesterday, I listened to some of a wonderful reading that Brooks gave when she became poet laureate at the Library of Congress. She began by reading three poems by girls from Chicago that had been submitted as part of the programs she ran as poet laureate of Illinois.

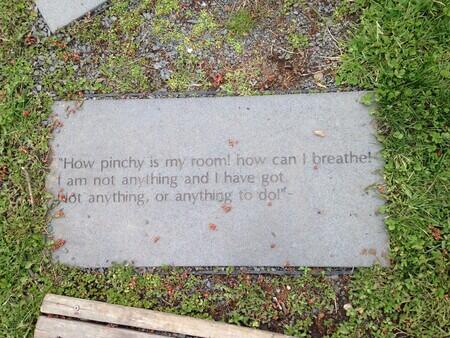

Annie Allen is difficult, and, at the same time, many of the lines make complete sense to children. When we take our children to Gwendolyn Brooks park, we sometimes read out the quotations that are on the stones. They both like the first one:

How pinchy is my room! they say, with a lot of relish. The rooms of our house are not that narrow, and we are grateful for that. At the same time, it is a phrase that makes a new stronger sense at the moment.

Annie Allen begins with a memorial poem for Ed Bland who was killed in Germany on March 20, 1945 – seventy-five years ago this spring. Then begins the first real section which is called Notes from the Childhood and the Girlhood. The line appears in the first poem, in which Annie Allen is born, the poem is called “the birth in a narrow room.” I am going to type out the poem at the end of this entry.

On Monday, I walked up to Gwendolyn Brooks Park on my own – it was very cold. I wanted to take a few more pictures of the sculpture, but a mother was standing near it with her child. The child was wearing a brown jacket with the hood up, and running up and down on the stones, and putting out her or his arms like an airplane. The installation also originally had some wooden hassocks arranged in a circle around the poet, to invite sitting to listen to her think, maybe read. These hassocks have mostly come apart, there is one and part of another still there. The child in the brown jacket sat on the remaining one and looked up at Gwendolyn Brooks and for a while I stood in the corner of the park and watched them in their private colloquy and then I turned and walked home.

*

Weeps out of western country something new.

Blurred and stupendous. Wanted and unplanned.

Winks. Twines, and weakly winks.

Upon the milk-glass fruit bowl, iron pot,

The bashful china child tipping forever

Yellow apron and spilling pretty cherries.

Now, weeks and years will go before she thinks

“How pinchy is my room! how can I breathe!

I am not anything and I have got

Not anything, or anything to do!”—

But prances nevertheless with gods and fairies

Blithely about the pump and then beneath

The elms and grapevines, then in darling endeavor

By privy foyer, where the screenings stand

And where the bugs buzz by in private cars

Across old peach cans and old jelly jars.