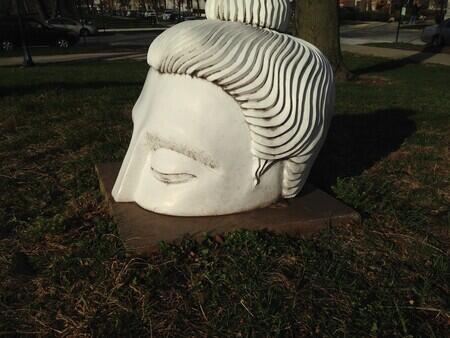

Emerging Buddhas 56th Street

Sunday, November 22, 2020

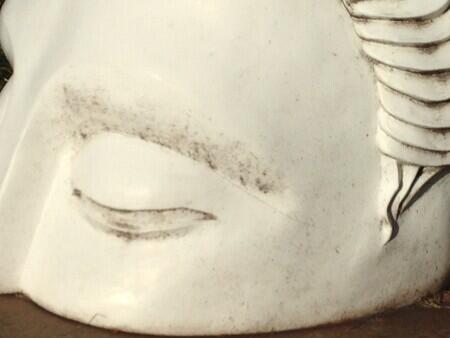

Ten Thousand Ripples, Indira Freitas Johnson and the Changing Worlds Project, 2016. Installed in Jackson Park between E. 56th Street and E. 57th Drive near the Iowa Building. Photos Rachel Cohen.

This time I was quicker to turn to public art. Knowing that the museums were closed again, I right away started walking to look at the sculptures and murals in our neighborhood. On Thursday, I spent a little while with a circle of sculptures that I’ve never really stayed with, though I always point them out to the children as we walk by, or ride on our bicycles.

They are in the green between 56th Street and 57th, just north of the Science Museum and near to the sloping downhill entrance that lets you get under Lake Shore Drive to Promontory Point, where there is a little stone building called the Iowa Building.

A circle of emerging Buddhas.

I would say they come up a little above my knees, large but well within the frame of a body.

In the original version of the Ten Thousand Ripples project, which began in 2010, there were 100 Buddhas in ten different neighborhoods in Chicago. A booklet was published and is available on the internet about the different people who took a lead in organizing in different neighborhoods. There are moving essays and reflections by a teacher, a permaculturist, a filmmaker, a community artist about working with the sculptures and people in the neighborhoods to think about peace.

The teacher is Jequeline Salinas, she is a visual arts teacher at Hedges Elementary School in Back of the Yards, which is in an industrial area on the west side at 47th and Ashland in a neighborhood that is 95% Latino and 5% African American.

Salinas was quoted in the booklet saying “This helped us in the healing process and the understanding process—and, really, the wondering process. It was something that really took us by heart—it really touched us.” Of course then I could see this was a person of beautiful and significant thought – the wondering process, and “it took us by heart,” – and so I have been scouring the internet for information about Salinas’s teaching practices and feel pretty persuaded that she is a genius.

In the booklet, she described a student who asked to be interviewed for a video project. “She was so shy—she never talks! So I took her out into the gallery space and asked if she knew what an interview was. ‘Yes,’ she said. So I said, ‘what would you say?’ She said, ‘When I see the Buddha, it reminds me that I need to talk.’ When I asked why, she said, ‘Because it doesn’t have a mouth.’”

***

Ten Thousand Ripples was conceived by the artist Indira Freitas Johnson, who has lived in Chicago for some twenty-five years and who grew up in India, where her mother was a social activist and her father a follower of Gandhi. The circle in our neighborhood was installed in 2016.

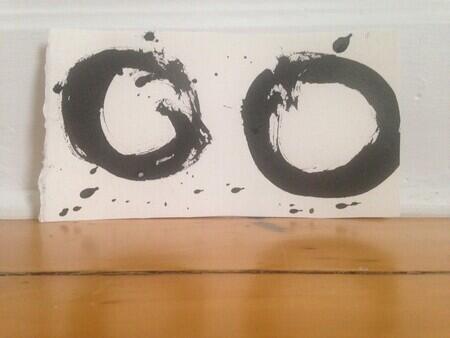

In different Hindu and Buddhist traditions circles are important for wisdom, expressivity, understanding – five Buddhas may be shown in the circle of a mandala, or, in Zen Buddhism, a circle of ink may be drawn in one or two brushstrokes as a practice for letting the mind be free, the body creative.

Enso Circles, Tara Geer c.2013. Photo Rachel Cohen.

I keep these, done in ink on heavy paper near me on my desk. They were made (what is the right verb for how these were made – drawn, swept) by the artist Tara Geer, who is someone I look to.

I thought I would like to write a sentence about when I began thinking about Buddhism. I asked myself when that had been. It was around the time that I met Tara, around 2000 and 2001. I was then in a relationship with a man whose family was from Calcutta and who had grown up in Zimbabwe. He wanted to see the Dalai Lama when he came to New York. And, when I asked myself the question, when did I begin to think about Buddhism, the memory arose in my mind, the sloping green of Central Park, and the people gathered there.

There were people from everywhere of course, but there were many Tibetans, long away from their homeland, for whom this occasion had its own meanings. As we sat in the grass, I had observed many women in the beautiful Tibetan garb, with pangden aprons woven in three panels of horizontal stripes, the pattern of which would tell the practiced eye what village and region they had been from.

When the Dalai Lama came on to the stage, all those who knew to do so, all the Tibetans and the other practitioners, stood and made an obeisance. It was so beautiful, radiant and outpouring. The joy in being with one another. We were all there.

I remember that I was struck by how funny and witty he was, and saw how laughter and wisdom were a part of one another for him.

And I was moved by what he said, and resolved to think about it, I felt very privately about it, something very private happened among all those people.

I find from the internet that it was August 15, 1999, that there were 40,000 people on the East Meadow. It was reported in Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine that the Dalai Lama said of spiritual development, “what is important is the development of inner peace. Compassion is a sense of caring, thinking about others’ welfare. This is linked to inner strength… Through constant effort, we can change our mental perception, our mental attitude, and that makes the difference in our life.”

After I stood among the emerging Buddhas near 56th Street, I went to the dentist, where I was nervous about virus exposure, though every precaution was being taken, and I was extremely impatient that they kept me waiting and complained vociferously to the hard-working and anxious people there about their disregard for my time, and rushed home to manage my correspondence and to prepare for a public conversation I was to have on zoom.

But I had stood in a future memory of peace, held in that circle that the artist and the people working in the neighborhoods of Chicago had made.